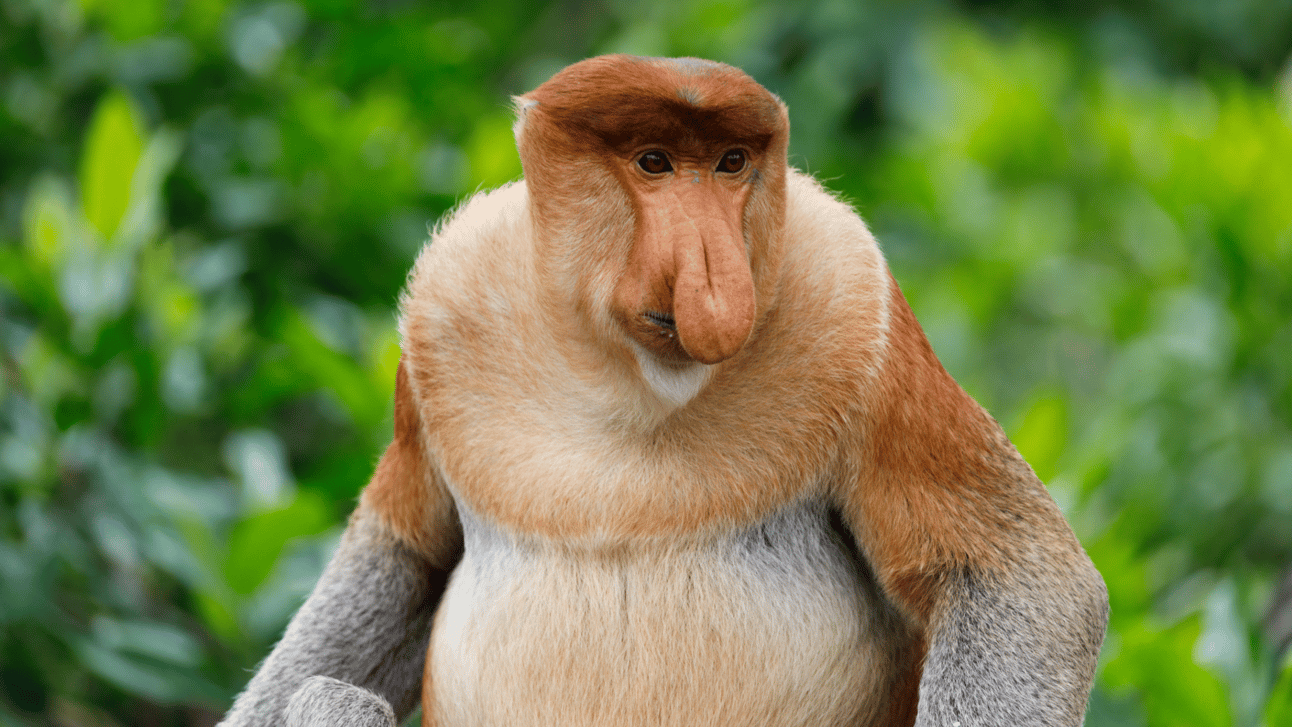

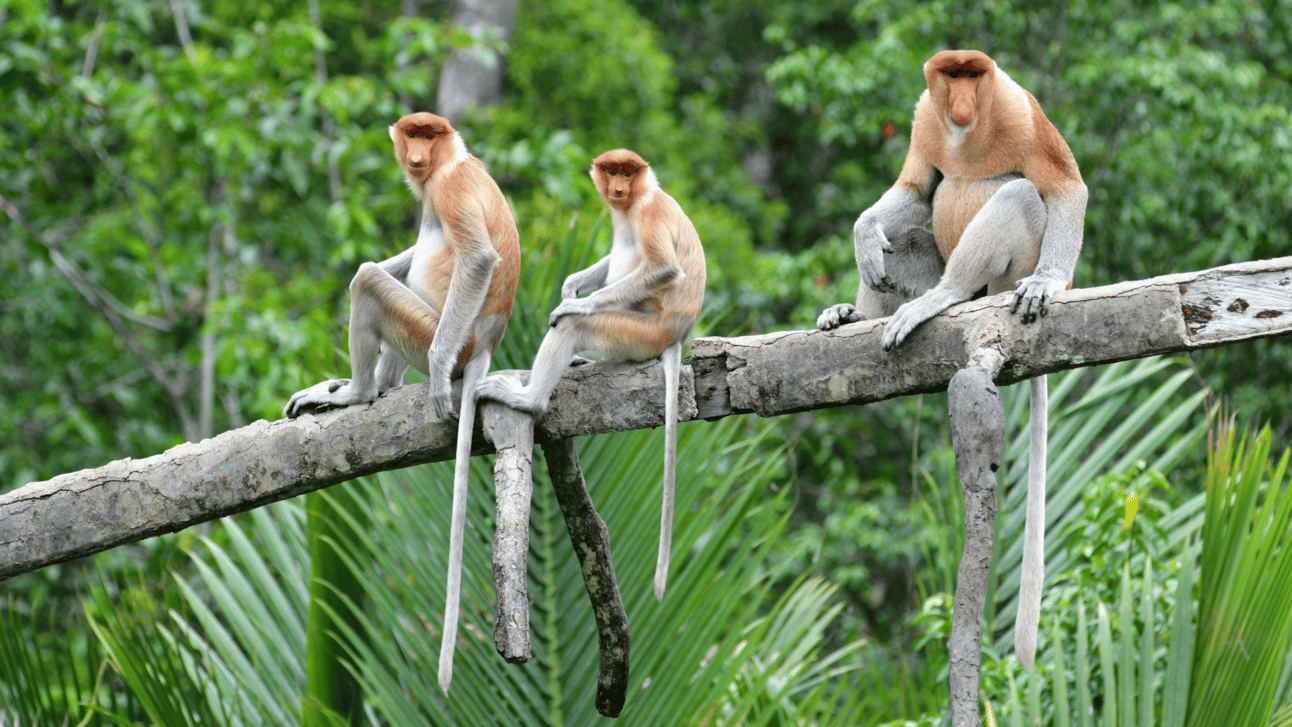

A dominant male proboscis monkey has an enormous, pendulous nose. These monkeys are also known for their potbellied physiques and partially webbed feet, which make them incredible swimmers. These endangered primates are endemic to the island of Borneo.

The Nose Knows

A large male’s nose can reach up to 17 cm (6.5 in) in length. The supersized noses amplify the males’ calls to attract mates and intimidate rivals. Scientists have found that males with larger noses also tend to be larger overall, with more developed digestive organs and testes.

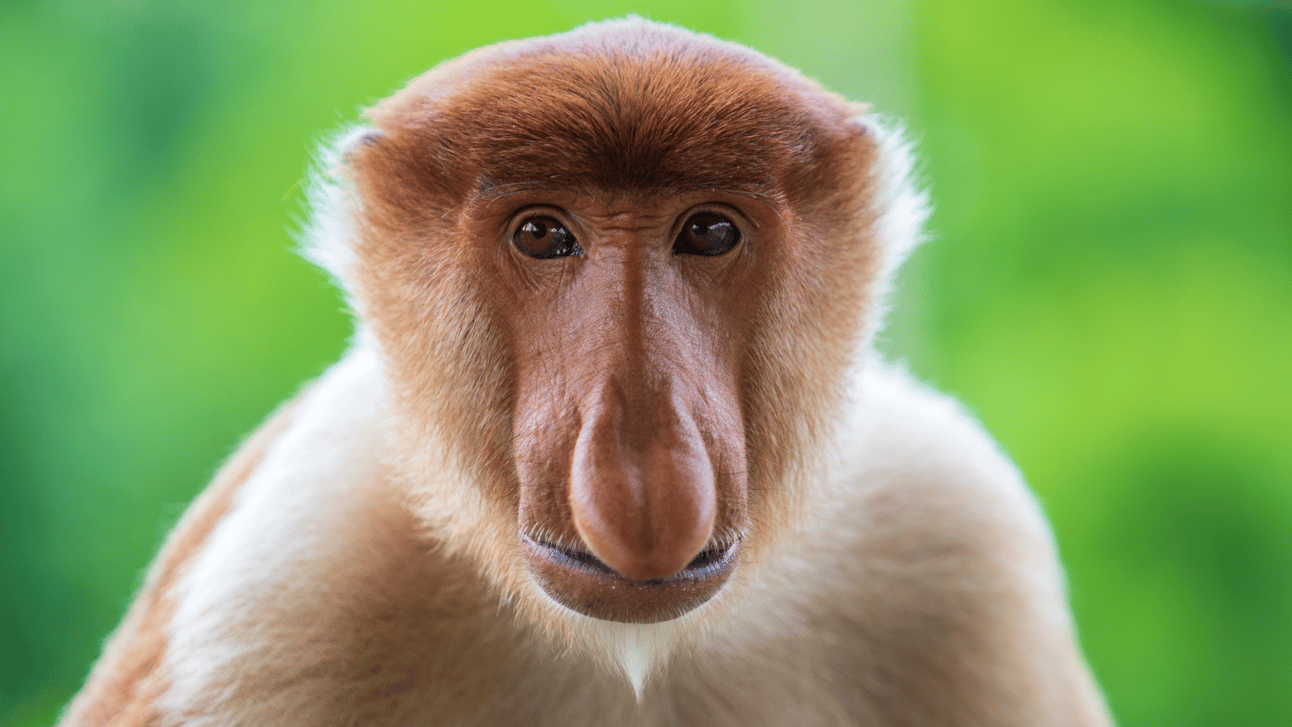

Only male proboscis monkeys develop such an elongated nose. Females and juveniles have much smaller, upturned noses. This difference between sexes is a classic example of sexual dimorphism. The males’ noses help project loud calls through the rainforest. These low, resonant calls serve to mark territory and keep the group together, especially when visibility is low in the mangrove forests.

This post is for paid subscribers

Get full access to this post and everything else we publish.

Upgrade to paid